|

|||||||||

| :: Issues > Islamic Movements | |||||||||

Is the "Brotherhood" with America Possible?

The way the Muslim Brotherhood views the United States

Unlike other Islamic political groups, the Muslim Brotherhood is a pragmatic movement that relates in a level-headed manner with regional and international powers

|

|||||||||

| Tuesday, October 2,2007 05:52 | |||||||||

|

|||||||||

|

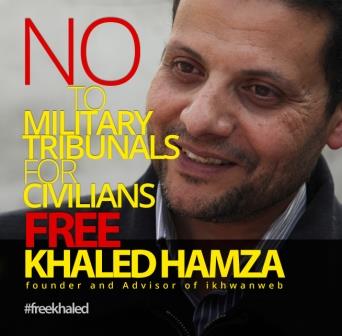

"There is no chance of communicating with any U.S. administration so long as the United States maintains its long-standing view of Islam as a “real danger,” a view that puts the United States in the same boat as the Zionist enemy. “We have no pre-conceived notions concerning the American people or the U.S. society and its civic organizations and research centers. We have no problem communicating with the American people but no adequate efforts are being made to bring us closer”, said Dr. Issam al-Iryan, chief of the political department of the Muslim Brotherhood in a phone interview. First Problem: The way the Muslim Brotherhood views the United States Second Problem: Doctrinal and other considerations: Muslim Brotherhood’s Dr. al-Iryan concurs with this overarching view of the West and expresses the following opinion of the United States: “It is difficult to speak of a civilization in the usual sense when talking of a country that’s less than 200 years old. Even assuming that the United States is a civilization, it is one that has been born out of exclusionist tendencies and through the eradication of the Red Indians. It is also a ‘material’ civilization based on the twin pillars of money and power,” he says.[5] The same view is echoed by Dr. Mohammad Habib, first deputy chairman of the Muslim Brotherhood general guide, who believes that the U.S. civilization is based on “survival for the fittest” as well as on double standards, especially when it comes to the issues of democracy and freedom.[6] The political angle: The Muslim Brotherhood views the United States as an occupation force. Mahdi Akef speaks of the United States in the same tone al-Banna used when talking about the British, French, or Italian occupation of Arab countries. In fact, al-Banna once wrote that “the days of hegemony and repression are over. Europe can no longer rule the East with iron and fire. Those outdated practices do not tally with the course of events, with the development of nations, with the renaissance of Muslim people, or with the principles and feelings the war has created.” Akef could use the same words today, but only in reference to the United States. Both al-Iryan and Habib agree that the United States wants to manipulate the Arab region to promote its own interests. The invasion of Afghanistan and Iraq are seen as evidence of U.S. intentions, the two would argue. The Muslim Brotherhood is critical of the United States’ close links with Israel and believes that the United States and Israel share the same political agenda. Mahdi Akef rails against the “U.S. and western bias towards the Zionist entity.” Habib says both America and Israel were founded on an ethos of forced expansion and colonialism. Al-Iryan puts it bluntly, “the main reason for our negative opinion of the United States is its ties with Israel. Its ties with Israel will remain a defining factor in our relations with the United States.” Third Problem: The course of relations Relations between the Muslim Brotherhood and the United States go all the way back to World War II, when the United States was about to inherit the British Empire and the Muslim Brotherhood was one of the most popular movements in the region. The British, acting with U.S. blessing, wanted to establish a rival group to compete with the Muslim Brotherhood. The new group, named Freedom Brothers, was supposed to attract the youths with its cultural, social, and liberal programs, but never quite made it. Afterwards, the United States began flirting with top Islamic figures in Egypt. At one point, a U.S. embassy official talked with al-Banna about cooperating against the prevailing communist threat, but the gap in views proved too wide to bridge. In the late 1970s, the U.S. sought the help of Muslim countries in organizing jihad-style resistance against the Soviets in Afghanistan. The Americans wanted Anwar al-Sadat to get the Muslim Brotherhood to fight the Soviets in Afghanistan, but the Muslim Brotherhood wasn’t enthusiastic. Later on, the Carter administration needed help with the hostage crisis in Tehran. The U.S. embassy asked Omar al-Telmesani, then Muslim Brotherhood general guide, to intervene and use his good offices with the Iranian President Ali Khomeini. With al-Sadat’s permission, al-Telmesani asked the Iranians to let him come to Tehran for talks. “You’re welcome,” Tehran’s answer was brief. “But we’re not going to discuss the U.S. hostages.” The visit didn’t take place. The Iranians waited till Carter lost the elections to Ronald Reagan and then released the hostages.[9] In the 1980s, relations between the United States and the Muslim Brotherhood improved as the United States, with Saudi mediation, sought closer ties with Islamic political groups in the region as part of its quest to drive the Soviets out of Afghanistan. However, the Sept. 11 attacks represented a watershed in the relations between the Muslim Brotherhood and the U.S. administration, so much so that one can speak of both a pre-Sept. 11 phase and a post-Sept. 11 one in their relations. 1. The pre-Sept. 11 phase: This phase covers most of the 1990s. In 1995, the Muslim Brotherhood won some seats in the People’s Assembly, and reports spoke of exchanges between the Muslim Brotherhood and the U.S. embassy in Cairo. Former U.S. Amb. Daniel Kurtz said that he met Muslim Brotherhood officials or people representing them.[10] Some Muslim Brotherhood members denied the reports at the time, but others confirmed them. The talks didn’t amount to negotiations, since the Muslim Brotherhood had nothing to negotiate about, but involved an exchange of views as Muslim Brotherhood General Guide Mamoun al-Hudeibi said at the time. [11] Furthermore, Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak confirmed the meetings when he said in 1995 that Washington had exchanges with the Muslim Brotherhood, which he described as a “terrorist” group.[12] The Egyptian regime consistently attempted to undermine any form of rapprochement between the Muslim Brotherhood and the United States. And it was in that same year (1995) that the Egyptian government arrested a large number of Muslim Brotherhood leaders in connection with what became known as the Salsabil Case. Several Muslim Brotherhood leaders were sentenced to three to five years in prison, including the current General Guide Mahdi Akef, al-Iryan, Habib, and Khyrat al-Shatir. The post-Sept. 11 phase: In this phase, the United States turned against many Islamic political organizations, mainly those engaged in acts unbridled of violence. But the difference between moderate groups and violent ones was not always clear for U.S. policy makers. When Hamas won the Palestinian elections, the United States reversed its earlier rhetoric about democracy. Up until the conclusion of the Palestinian elections, the United States was sending positive signals to the Muslim Brotherhood and all moderate Islamists. Bush and Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice both suggested that a moderate Islamic government anywhere in the Arab world would be acceptable to the United States. Here are a few samples of this view: - Speaking to the U.S. Council on Foreign Relations, Richard Haass, director of policy planning for the U.S. State Department, said that the United States does not oppose Islamic parties and knows that democracy may bring Islamic parties to power, due to the fact that the latter were the best organized opposition groups around.[13] The remarks were in recognition of the political gains the Islamists were making in Turkey, Morocco, and Bahrain. For its part, the Muslim Brotherhood didn’t mind holding meetings with U.S. government officials. Al-Iryan says that the Muslim Brotherhood was willing to engage in dialogue with the United States, referring to similar statements he made to Agence France Presse to this effect, following the 2005 parliamentary elections. “The Muslim Brotherhood position is that we believe in dialogue and in cooperation among civilizations, so long as it is conducted on an equal footing. We also believe that there are common values that bind all cultures and nations.”[16] Nonetheless, the Muslim Brotherhood insists that a representative of the Egyptian Foreign Ministry be present in all Muslim Brotherhood meetings with U.S. officials. This is what Akef told Al-Sharq Al-Awsat on Dec. 11, 2005. “Any such meeting should be arranged through the Egyptian Foreign Ministry,” he said.[17] This precaution is designed to allay the Egyptian regime’s fear of exchanges between the group and the Americans. The Muslim Brotherhood also wants to make sure that the Mubarak regime is not going to use its contacts with the Americans to tarnish its reputation. No direct dialogue existed between the Muslim Brotherhood and the Americans in this phase, but the relations between the two were fraught with optimism. The U.S. and the Muslim Brotherhood sought out ways to circumvent the regime’s reservations, perhaps through the intercession of Muslim Brotherhood parliamentarians. However, things changed after Hamas won the Palestinian parliamentary elections on Jan. 26, 2006. The Hamas victory revived old U.S. fears that a tide of radical Islam was sweeping over the region. Since then, there have been no reports of U.S.-Muslim Brotherhood exchanges. Hamas, originally started out as an Muslim Brotherhood group. So the United States cannot claim to be in good terms with the Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt but unable to talk to Hamas. Interestingly enough, the United States refrained from denouncing the arrests of Muslim Brotherhood leaders in Egypt following the group’s impressive performance at the March 2006 elections. For the time being, the United States seems to be revising its ideas about democracy in the Middle East. Fourth Problem: The impediments of dialogue Even if the United States and the Muslim Brotherhood were serious about talking to each other, several issues still hamper the chances of having a fruitful dialogue: Fifth Problem: Prospects of dialogue The impediments mentioned above would seem to preclude a dialogue between the United States and the Muslim Brotherhood. But the need for the United States and the Muslim Brotherhood to talk with each other may prove greater than all existing impediments. It is true that the ideological differences between the United States and the Muslim Brotherhood are unbridgeable, but self-interest may leave much to talk about. Still, any future dialogue would remain unlikely unless a few things happen first. One is that the United States would need to talk to the Egyptian regime about its repression of the opposition, including the Muslim Brotherhood. Another is that the United States should acknowledge – yet again – that democracy may bring the Islamists to power. Also, the United States would have to distance itself somehow from Israel, for no Islamic group would want to associate itself with Israel’s alter ego. U.S. officials can actually meet with Muslim Brotherhood parliamentarians, which is already happening, but all interaction can occur on a more regular basis. This is because the U.S. Congress can, for example, invite Egyptian parliamentarians, including Muslim Brotherhood members, for an official visit. This study was published at Arab Insight journal at: [1] Telephone conversation with Issam al-Iryan on Friday 2 February 2007. [4] The weekly address by the General Guide, from ikwanonline, 3 January 2007. |

|||||||||

|

Posted in Islamic Movements , Research |

|||||||||

|

|||||||||

|

|

|||||||||

| Related Articles | |||||||||

|

|